“Fraud is a trillion dollar problem, about $5 trillion today with that number increasingly rising annually.”

Show More Show Less View Video Transcript

0:00

Fool Me Once came about because I did a documentary years ago about a woman that embezzled $53.7 million from a small town

0:10

And I learned so much about myself, about people, about victims, about whistleblowers

0:18

And once I did the documentary, I felt like there was something more that I needed to explain to the general public about fraud

0:25

how it happens, how people commit it, how people whistleblow about it. And so that was really the

0:32

birth of Fool Me Once. It really was a self-reflection because I've had so many experiences

0:37

with fraud cases. And so fraud cases include a perpetrator, a victim, and a whistleblower

0:45

And so I like to refer to them as perps, praise, and whistleblowers. So those are really the three

0:50

my three indices of fraud. And so the book really dives deeper into what type of perpetrator or the

0:58

various types of perpetrators you could be, the various types of prey you could be, and the various

1:03

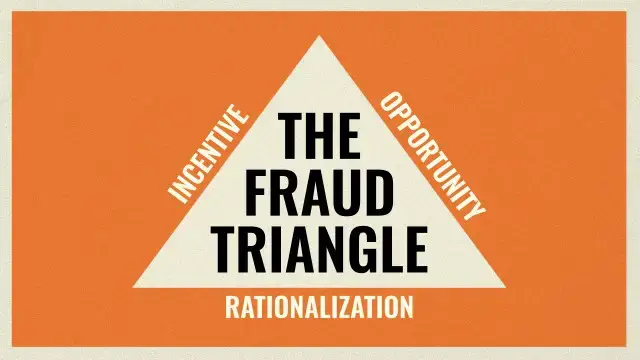

types of whistleblowers. The Fraud Triangle, understanding why good people do bad things

1:11

One thing that a friend told me that I'm just going to steal their line, and they said fraud

1:16

never sleeps. And it's really a global problem. Fraud is a trillion dollar problem, about five

1:23

trillion dollars today with that number increasingly rising annually. So it affects everybody, every

1:29

industry, every country, you name it, there's fraud. If there are people, there could be fraud

1:36

And so for that reason, no one is immune to it. And so I think what attracted me originally to

1:42

the subject is how universal it was. There's no one that you can walk up to and say, are you not

1:48

concerned about fraud? Everyone is. And so that just fascinated me, really the behavioral aspects

1:55

of fraud. So when I started studying fraud years ago, I was introduced to the work of Donald Cressy

2:02

And Donald Cressy is known as the criminologist that introduced the fraud triangle. And the fraud

2:08

triangle has three indices, opportunity, rationalization, and pressure. And I was always

2:14

fascinated by the rationalization component of the fraud triangle and always felt that there needed

2:19

to be more research there. A lot of times what Cressy's work focused on was embezzlement

2:25

which is one type of fraud. And he often talked about that the reason why people engage in fraud

2:32

is a lack of morality. And it's so, it's more complex than that. And so that was really what

2:38

my passion really drove me. And I started going around the country and doing on-camera interviews

2:46

with white-collar felons, whistleblowers, and victims of fraud because I wanted to understand

2:50

more about that rationalization component because it explains so much. It helps us learn about how

2:57

we can protect our organizations when we can understand how a person rationalizes these types

3:02

behaviors? I think fraud is a victimless crime because we often have a definition about what we

3:11

think a crime is. So I physically attack someone or I physically steal something from someone and we

3:17

think that's a crime. A lot of times fraud is victimless because there's some research that

3:22

talks about the psychological distance between an act and a crime. So if there's more distance

3:31

between you and what you are stealing, then you sometimes think it's victimless. For example

3:37

I remember reading a study, I think it was Dan Ariely, his research, and he was talking about

3:43

how people behave when they're thinking about cheating and golfing. And he surveyed some people

3:50

and what he found was people were more in agreement to cheat if they used a golf club

3:56

to move the golf ball than if they've used their hand. And so what he's describing is this psychological distance

4:03

between what it means to cheat. So a lot of times people think making an entry

4:08

or booking a false entry is not the same thing as stealing money out of someone's purse or someone's wallet

4:15

And so I think that's what allows us to say, it's okay for me to book this

4:21

because there's no human being actually associated with it. We don't see them

4:25

We don't have to explain anything to them. So I think it makes it easier for us to say, I want to overstate revenue and understate expenses

4:34

And it's OK because no one's really going to get hurt. It's just a company

4:38

But we don't think about that company leads to people that leads to people's jobs that then leads to people's ability to take care of themselves, take care of their families

4:47

We don't think about all of that when we think about that one number showing up on a financial statement

4:53

When I started thinking about my own experiences with fraud, and specifically perpetrators, I started to do some research

5:03

And the simple rationalization of crime is a really interesting concept because what it says is the bigger the reward, the more likely we are to steal

5:13

And I'll give you an example of what I mean by that. I remember one day in class, a lot of times before I talk about fraud, I don't use the F word

5:22

I don't say fraud. I'll give them an example. And so I went in class and I said, what if you walked in today and you saw a bag of money sitting at the front desk

5:32

What would you do? So everyone sort of looks around at each other because no one wants to say anything at first

5:37

And so I said, just tell me what your thoughts are. You see this bag and there's just money pouring out of the bag

5:43

What do you do? What do you think? And they start thinking and I start to start to write their answers on the board and they'll say

5:50

well, how much money do you think is in the bag? They'll ask, does the room have cameras

5:56

They'll ask, how old am I? Have I passed a CPA exam? Am I married? Are my parents alive

6:01

And so what they're doing, what my students are doing, these are graduate students, is they're rationalizing if it's worth it for me to take. And so if that reward is big enough

6:11

then I'm going to risk it. I'm going to take it. I'm going to try. And so that's typically how I

6:16

introduce the rationalization component when I'm teaching students because I want them to see how

6:22

relatable it is for any of us to rationalize why it's okay to take something. So when I'm with

6:29

when I read a good fraud case, I think about what type of perpetrator it is because there's a

6:36

there's this misconception that all perpetrators are the same. People steal for greed and that's

6:42

not true. There are different reasons why people can engage in fraud, why people become perpetrators

6:48

And so when I was thinking about the book, I was thinking about my roller coaster of emotions that

6:53

I've had. I have interviewed perpetrators and I just empathize with them. But then I've interviewed

6:59

other perpetrators where I'm just angered by what they've done. And so that made me think there are

7:05

how can I advance a theory where there are different types of perpetrators and force people

7:11

to understand that all perpetrators are not the same. So I came up with these three

7:16

intentional perpetrators, accidental perpetrators, and righteous perpetrators. Now, intentional perpetrators is what we binge when we watch Netflix, when we watch Amazon Prime

7:29

I mean, it's what the movies are made of. You can name any show that you're watching now that's a

7:34

true crime show. It's about an intentional perpetrator. But the accidental and the righteous

7:39

perpetrators, those categories should make you feel a little bit more uncomfortable because

7:44

you may relate to them in a way that you never imagined that you would

7:50

What I've noticed with the intentional perpetrators I've interviewed over the years is they're

7:55

so likable and they charismatic and they like they draw you in and you just you just sort of get in this trance of of hearing their story You sort of scared of them at the same time but they charismatic so they can work a room

8:13

And a lot of times I don't ask them if they're remorseful because maybe I don't believe what they're going to say

8:20

but I don't ask that question because I think that a lot of times they're angered that they got caught

8:26

And so they may have continued whatever the crime was, but because they got caught, if it was a whistleblower, whatever the reason is, that tends to be the emotion that they're referring to

8:39

I mean, if you ask the question, are you upset that you did it? They're going to say yes because they're going to jail for 3, 10, 20 years

8:45

So I tend to not ask that question, especially if I understand the scheme that they were involved in

8:50

But one of the characteristics that I've noticed through the years is just how likable they are

8:57

And so all of the perpetrators I've interviewed over the years, they become like friends because you learn so much about their lives

9:08

And so the intentional perpetrators, their stories are wild. Their personalities are big

9:15

And they're very forthcoming about, hey, this is what I did. This is why I did it

9:19

I'm going to share it with you. I'll share it with your students. I wouldn't do it again, but maybe. You know, they sort of always

9:26

say those kinds of things. And so you just don't understand it. But it's this wild feeling that

9:32

you have about them. And it's why we're so addicted to the stories. So some of the most infamous

9:39

intentional perpetrators, Bernard Madoff, the Enrons of the world, Jeff Skilling, these are people

9:48

that set out to defraud. They know all the internal control weaknesses inside an organization

9:53

and they tend to be pretty savvy, pretty arrogant, pretty confident. And notice these are traits that

10:01

we tend to admire in a corporate structure, but they are the type of people that they'll ask for

10:10

forgiveness. They'll just go forward and ask for forgiveness later. That tends to be the profile

10:16

of an intentional perpetrator. So they tend to have a significant level of authority

10:22

in the organization because it allows them to advance whatever they're trying

10:27

whatever idea they're trying to advance. So when you think about Madoff and you think about that fraud, Madoff was powerful

10:35

No one questioned him. Everybody wanted to be invested in his fund

10:39

and there were very little internal controls around him. What he said is what happened

10:44

And so he's a he's a good, well-known intentional perpetrator. Now, in my documentary, All the Queen's Horses, the perpetrator there was this woman by the name of Rita Cronwell

10:55

Now, she might not be as well known, but Rita Cronwell is known as the largest municipal fraudster in U.S. history

11:04

And so she's a primary intentional perpetrator, someone that knew the system inside and out

11:11

She was a city comptroller of Dixon, Illinois. And so everyone trusted her. No one questioned her

11:18

I think the way she lived, she was likable. She was that person that she would receive your invitation to your party, to your to your wedding

11:28

And she sent you a nice gift. She was that employee that when she went on a trip, she'd bring you back a box of chocolates

11:33

So she was socially likable. No one ever said anything bad about her

11:38

I've been to Dixon multiple times. So many times I probably should have a place there, just a rental house

11:44

But she she always was described as a likable person. And I think you have to be likable to some degree in a corporate structure to be able to engage and hide a fraud for a very long time

11:57

Now, in Rita's case, fifty three million dollars over 20 years. You got to be a little likable to keep that going for so long to keep people at bay

12:05

And so why did Rita need $53.7 million for quarter horses? Not only did she buy horses, she owned over 400 quarter horses

12:15

400. That's a lot of horses. It's very expensive to have an operation like that

12:19

She had real estate. She had cars. She had jewelry. Just anything you can imagine

12:28

And this is the typical profile of an intentional perpetrator. They have an endless supply of money from the organization that they're stealing from

12:36

And Rita did it for 20 years. And so intentional perpetrators are different than con men, though

12:43

So they don't set out to just think about how I can defraud every person that walks down the street

12:48

They know their organization well. They know the internal control weaknesses inside the organization

12:54

And they use that and exploit it for personal gain. That's an intentional perpetrator

12:59

And they are, in my archetype system, they're the most dangerous because when they have power, they typically have access and they can have it when they want to

13:12

So just think about how the Madoff scandal impacted thousands of millions, well, millions of dollars, thousands of people

13:20

Another well-known intentional perpetrator that you may have heard of is Sam Bakeman-Fried, really classic intentional perpetrator

13:29

I'm someone who knew how to exploit the system. No one ever asked questions. People just invested in his in his exchange and no one seemed to question anything

13:40

So those are examples of intentional perpetrators. And again, we are addicted to their stories

13:46

Now, the question is, why? Why are we so addicted? Are we do we question? Could we do what they did

13:53

Is it that they take so much? Is it that so many people just watch them do what they do and no one stops them

13:59

There's a reason why we're addicted and there are there's a reason why these stories are so popular

14:04

But intentional perpetrators anger me because I don't understand why the auditors don't stop them, why the employees can't stop them, why the board doesn't stop them, why the audit committee doesn't stop them

14:18

I mean, why does why do they keep rising to the surface

14:22

And so it angers me. And so I have those intentional perpetrators come to my class, talk to my students

14:27

I go around, do on-camera interviews with them because as much as they anger me, they

14:32

fascinate me too. So we were talking about intentional perpetrators. We're going to switch gears and compare the polar opposite kind of person, which is a

14:41

righteous perpetrator. Now, granted, all perpetrators broke the law and they go to jail

14:47

We all understand that, but we're really thinking about why did they do it

14:51

And so the righteous perpetrator was a category that was inspired really from my own personal

14:57

fraud story as a child. So I grew up in Durham, North Carolina. And years ago, when I was in high

15:03

school, my neighbor was sentenced to federal prison for money laundering and embezzlement

15:10

And this family had everything. He had a nice car, nice house, wife, kid, dog, picket fence

15:18

you name it. They had it all. And so when I overheard my parents talking about this fraud

15:25

case, and I was younger, but I was even nosy back then because when my parents were talking

15:29

I was just like, what did the neighbor do? Anyhow, so when I started looking and reading about this

15:36

case, what was really fascinating is his rationalization. The reason why he did it

15:41

not for personal gain, but to help a friend. He wanted to help a friend's business. So there are

15:48

people that will engage in fraud to help a family member, help a friend, help a colleague at work

15:56

Granted, we know they committed a crime and they went to jail, but we're really talking about why

16:01

they did it What I noticed about the righteous perpetrators those stories when those perpetrators come to my class my graduate students are holding on to their every word and they empathize with them in a way that they do not show with an intentional perpetrator

16:18

So intentional perpetrators, they may be angered, but that righteous perpetrator, their heart goes out to them because

16:25

well, they were doing it to help a friend. They didn't mean to do it. They didn't even get any money from it

16:30

but they were just trying to help. I spent some time at a conference

16:33

and during the conference, I went to visit a women's prison and I wanted to talk to some inmates who had engaged in fraud

16:43

And so I met this woman who, and her story's in the book

16:47

but I met this woman who was in prison for, I believe, six to eight years

16:53

because what she wanted to do was help the residents in her community

16:57

because she looked at her boss, and her boss was a person

17:01

that was charging really high rents and not giving her neighbors good quality living

17:10

And she felt like she had the power to right a wrong. And so what she started to do was to create

17:16

fictitious invoices so that her friends, her fellow neighbors could get jobs so they could

17:22

survive. And so when the money didn't add up and her boss was wondering, why don't I have enough

17:29

money in my bank account, where are things going? And she couldn't really answer that question

17:34

He realized that she had created fictitious invoices and was embezzling from his organization

17:40

Now, why was she doing it? To help other people. And when I sat down with her, she was actually

17:46

proud of what she did because she was helping others. Sort of like the Robin Hood syndrome

17:52

you know, rob, steal from the rich to give to the poor. She was exactly that person. And she was

17:58

proud. And this woman, she was married, she had kids, and yet she felt like she was doing

18:04

a public service by doing this to help the community. Another example of a righteous

18:10

perpetrator, and she just, her story just sits on my heart so close. This woman by the name of

18:16

Kayla Rivello, her story's in the book as well. And Kayla was a Wall Street corporate lawyer

18:24

I mean, she was an equity partner at some of the top law firms on Wall Street

18:31

And she had power, she had privilege within her organization, and people trusted her

18:36

And so Kayla had the opportunity to hire outside vendors to do some of the work that her law firm was engaged in

18:44

And what she decided to do was hire her husband. Now, some of us might not think, well, that's not fraudulent, maybe nepotism, but it's not fraudulent

18:53

I'm just going to help a friend. You know, we refer business all the time. Doesn't seem wrong

18:58

right? Probably not. So she didn't tell anybody that the firm that she recommended was her

19:04

husband's firm. So she had an inclination that probably I should keep that a little bit secret

19:09

But what happened is he was awarded a contract. It was a printing contract because she was doing

19:15

her company was doing litigation cases. And so there was a lot of photocopying involved. And so

19:22

her husband's copying business got the contract. Things were going fine until he started submitting

19:30

phony invoices for work that had not been done. So Kayla was in a tough place because I didn't tell

19:39

my partners that my husband was doing the work and now my husband is not doing the work and I'm

19:45

trying to save my marriage and keep everything together at home. What do I do? Kayla had the

19:50

power to approve the invoice. Should she approve or should she not? So what do you think she did

19:55

She approved the invoices, the fictitious invoices. Now, this is a really long story

20:01

And my only point here is the only reason why she did this is to help her husband. She was an equity

20:07

multimillion dollar partner. She didn't need the money and she was trying to preserve her marriage

20:14

And long story short, he was arrested for something outside. You got to read the book to find out

20:20

He was arrested for something else he was doing. And when he was arrested and the police started looking into his life, they noticed, hey, your wife

20:32

First of all, her husband had this business that was making millions of dollars. And his wife was an equity partner at this law firm

20:41

And they started looking into her life and realized that this embezzlement scheme was in the making

20:48

and that's how they both ended up going to federal prison. Now, why did she do it

20:53

To help her husband. That's the only reason why she did it because she didn't need the money

20:58

Righteous perpetrator. And what's interesting is a lot of us may do something to help a friend

21:05

to help a family member, to even help a colleague. And we might not think initially

21:10

it would lead to prison, but it can. That's the righteous perpetrator category

21:15

So as I've interviewed and met righteous perpetrators over the years, I tell you, there are times when my eyes are swelling with just like holding back tears because I feel so bad for them

21:32

But what I've also noticed is the number of people that will help them

21:37

So there was one righteous perpetrator I interviewed years ago. Her name is Elise Dixon, and she was involved in a mortgage fraud scheme

21:44

And I won't go into the story, but what I will tell you is she had a great law firm offer pro bono services for her because she was a good person

21:55

They understood how it happened. She was trying to help a friend

22:00

And so what I've noticed about the righteous perpetrator category is people will help them

22:05

And a lot of times when you talk to perpetrators, they'll say, I lost friends

22:09

No one will return my phone calls. But when there are intentional perpetrators, that happens

22:14

But when they're righteous perpetrators, people come to their aid and help them and give them second chances

22:20

And so I've noticed I've just watched my students interact with the righteous perpetrators

22:25

They're the ones that are emailing them. They're giving them contact information

22:29

They even sometimes have given them like I saw this job announcement

22:32

Maybe it's something that you could do. They just go out of their way to try to help

22:37

And I think it's because they can empathize with what they did

22:41

not to say they would do the same thing, but they can understand how it happens

22:46

Now, if you were ever to be a perpetrator, and I know when I say that

22:50

that may make you feel a little uncomfortable, but if you were ever to be a perpetrator

22:55

it could be a righteous perpetrator or an accidental perpetrator. And those two categories should really scare you a little bit

23:03

because the likelihood of you being an intentional perpetrator is probably slim to none

23:08

But the likelihood of you wanting to help a friend, turning a blind eye to a transaction and being righteous perpetrator, that the statistics are higher there

23:19

And the accidental perpetrator should scare you even more. When I was thinking of this category, I want I was very strategic about using the word accident because an accidental perpetrator is somebody that they're a team player

23:35

They are a people pleaser. They don't rock the boat. You ask them to do something, they do it

23:41

They trust. They trust blindly. They are loyal. And that might sound like you

23:46

Think about this. If your boss, your supervisor asked you to do something and you trust them, you probably don't think twice about it

23:54

If they asked you, go and book this entry. We can reverse this entry next period

24:00

We just needed to make the financial statements look the way we need. We'll fix it later

24:04

You trust this person. You might do it. Now that entry that you book in your financial statements could be fraudulent And you not thinking about that because you have 100 trust in your supervisor command of you But it could land you in prison

24:22

Now, that's the accidental perpetrator dilemma that they find. They wanna please, they wanna follow the boss's orders

24:29

But what if the boss's orders are faulty? What do you do

24:32

Do you speak up? Do you say something? These are the people that sometimes just stay quiet

24:37

And this has happened to all of us. We can probably sit and think on one or two hands the number of times that we've sat in a meeting

24:46

someone's asked us to do something, and you're just like, nah, I'm not signing off on that

24:51

I'm not putting my name on that. But there might be a time that you didn't do that, and you put your name on it and hoped that nothing would go wrong

24:59

That's the accidental perpetrator. And that could be any of us. Any of us

25:03

And so there was a gentleman that I interviewed years ago. And the way I met him is his legal counsel reached out to me

25:14

And as part of his sentencing, they wanted him to share his story with students

25:21

And so somehow people knew that I was going around the country and doing these interviews with people

25:25

And his legal counsel reached out to me and I did this interview

25:29

And so Andrew Johnson was one of the nicest men I've ever met

25:34

I mean, the quintessential accountant. When you think of the word accountant, you would think of a picture of this man, khaki pants, like a collared shirt

25:44

I think he even had some pencils and pens in his shirt pocket

25:48

I mean, just what you would think an accountant would be super nice. And I remember when he sat down and he started sharing his story with me, I said to myself, how did he end up going to federal prison

26:01

Now, he was sentenced to nine months, a year and a day, and he served nine months, but he's still a convicted felon

26:08

And so I remember that story, and the impact that it had on me was this

26:14

His story was so scary to me, I never showed it to my students. I never even taught about the case because I was afraid that they would be so afraid and turned off from accounting that I never really taught and showed it to them

26:27

because what Andy did, he didn't get any personal gain. He was following his boss's orders

26:36

And his bosses really weren't interested in learning about accounting. They didn't want to know the details about accounting

26:41

They didn't want to hear about the accounting equation. They didn't want to hear any of that. All they wanted to know was make the numbers work

26:47

We're trying to be acquired. Just make it work. And that was what Andy's charge was

26:52

He was the person. He was the director of finance. And so they didn't want the details

26:56

They just wanted the summary. And so Andy ended up engaging in what we know today as earnings management

27:05

And he knew it was wrong, but he's trying to be a team player

27:11

He's trying to keep his job at the time. He had a wife that didn't work

27:17

He was the sole breadwinner in the household. He had to keep his job and he had a pretty good job

27:21

I remember him telling me he just built an addition on his house. So this was not a time to get laid off

27:27

So Andy made a couple of entries, engaged in earnings management, and about a year and some change later, the FBI came knocking at his door because he was working in a publicly traded company

27:41

And you can't engage in earnings management. Like it's just you can't lie about your earnings

27:47

Your earnings have to come from revenue generating operations of your business

27:51

And so you can't smooth the yearnings and say, oh, I'm going to make them look better than they should in this period

27:57

You can't do that. So Andy found himself spending or being sentenced to a year and a day in federal prison, served nine months in federal prison, but it destroyed his life

28:08

There's a lot of judgment that goes into the work of an accountant, especially a work, the work of a CPA, certified public accountant

28:15

And so the way you might be turned off when you hear Madoff's story is not the way that you'd be turned off when you hear about an accidental perpetrator story, because you see yourself in their stories

28:29

You understand the business struggles that they have. You understand the meetings that they're sitting into. You understand their pressure

28:37

And so you see it. And so when they get to that point, that decision point of I'm going to make this entry or I'm not going to keep quiet

28:45

I'm not going to push back. I'm not going to tell the safety team we shouldn't do this because it could cost lives

28:52

When you don't do that, you can empathize with the shoes that that person is in

28:57

That's the accidental perpetrator. I think what's really important for all of us to do is pay attention to corporate culture

29:05

And I know that's one of the common buzzwords that we hear about, but it is so important

29:10

The corporate culture that is lived and the corporate culture that is written about can be two different things

29:16

So we might talk about, you know, we're environmentally, sustainably, you know, ethically

29:22

They may use a lot of these buzzwords, but how do they actually act

29:26

What happens? And so when you are in an environment, especially an environment where there's rapid growth and expansion and that's the focus

29:33

sometimes the powers that be, the C-level, the C-suite executives may be willing to cut corners

29:41

They may not have sound internal control policies. They may not even have a sound accounting system to trace and track all the transactions

29:51

If you see that, be careful. You think about Sam Bankman-Free. Think about the organization there

29:59

If you walked into that organization and you knew that there was no policies, there's no expense reimbursement policy, you can just use an emoji and submit your request, your reimbursement

30:14

That is a red, red, red flag. I don't know what's more redder than red, but that is a red flag that you should be very careful of because that's telling you something seriously about corporate culture

30:26

Now, FTX might have talked about, oh, we're innovative and we're providing opportunities for banking outside of banking

30:34

They might have said all that, but how they actually operationalize their mission is very different

30:40

There were no controls. There was no accounting system. When you see things like that and you have a intact moral compass that you want to live by

30:51

be careful of engaging with an organization like that because they are going to push you

30:57

They're going to ask of you things that you may not feel comfortable doing

31:01

And so I'll use myself as an example. I'm a professor at DePaul University

31:07

DePaul is the largest Catholic university in the United States. And so knowing that there are things that I know that the university supports and there are things that I know the university does not support

31:19

If I don't support the same things that they support or don't support, maybe that's not the organization I need to be in alignment with

31:26

So you have to think about what you're getting yourself into when you align with certain organizations

31:32

So just pay attention because red flags wave in our face all the time

31:37

Sometimes we close our eyes. Sometimes we turn a blind eye, but they're there and they're there in every organization

31:43

Thinking about Andy, he was in an organization where no one wanted to hear about accounting

31:49

Now, I love accounting. I think everybody needs accounting in their life, just like you need water, air

31:55

I mean, I think it's like a thing we all need to know

31:59

But he was in an organization that no one cared. They didn't want to hear the details

32:03

And so when you are an officer and you have a fiduciary responsibility

32:09

being in an organization like that could be challenging. So you have to be aware and pay attention

32:14

Want to support the channel? join the Big Think members community where you get access to videos early ad free

#Legal