videocam_off

This livestream is currently offline

Check back later when the stream goes live

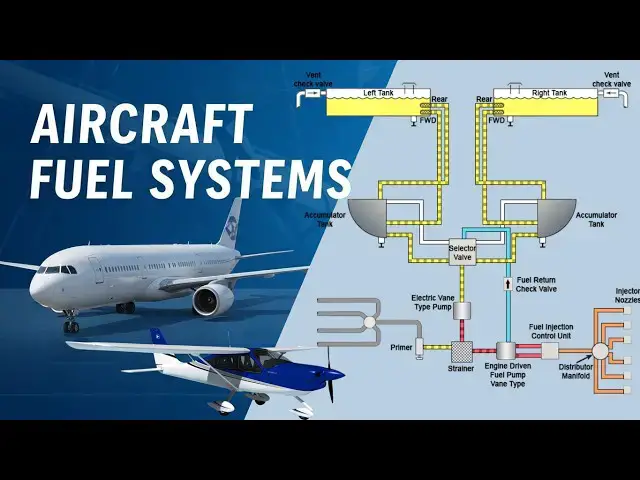

Aircraft Fuel Systems Explained | From Light Aircraft to Jet Transports & Helicopters

In this video, we explore aircraft fuel systems across a wide range of aircraft types—from small single-engine airplanes to large jet transport aircraft and helicopters.

You’ll learn how fuel is:

• Stored, vented, and protected

• Delivered at the correct pressure and flow

• Managed in gravity-feed, pump-feed, and fuel-injection systems

• Safely supplied during all phases of flight

•

The video covers:

• Fuel system requirements

• Fuel storage and refueling systems

• Types of aviation fuel (AVGAS and Jet Fuel)

• Small single-engine aircraft fuel systems

• Gravity-feed and pump-feed systems

• Fuel-injected aircraft

• Large reciprocating aircraft (DC-3 example)

• Jet transport aircraft fuel systems (with fuel jettisoning)

• Helicopter fuel systems

Show More Show Less View Video Transcript

0:07

The aircraft fuel system plays a

0:09

critical role in safe and efficient

0:11

flight. Its purpose is simple but vital

0:14

to store fuel and deliver the correct

0:16

amount of clean fuel to the engine at

0:18

the proper pressure. In this video, we

0:20

will study aircraft fuel systems step by

0:23

step, beginning with fundamental

0:25

concepts and progressing toward

0:26

practical aircraft applications.

0:31

The aircraft fuel system is designed to

0:33

store fuel and supply it to the engine

0:35

under all operating conditions. It must

0:38

function reliably during engine start,

0:40

taxi, takeoff, climb, cruise, descent,

0:44

and landing. The system must continue to

0:47

operate despite changes in altitude,

0:49

aircraft attitude, acceleration, and

0:52

atmospheric conditions. Every aircraft

0:55

fuel system must be designed to deliver

0:57

fuel at the correct pressure and flow

0:59

rate. So the engine and auxiliary power

1:01

unit operate properly in all normal and

1:04

certified flight conditions, including

1:06

maneuvers. To maintain safe operation,

1:09

each fuel pump is designed to draw fuel

1:11

from only one tank at a time, and the

1:14

system must prevent air from entering

1:16

the fuel lines. For turbine powered

1:18

aircraft, fuel systems must meet strict

1:21

fuel venting requirements and continue

1:23

operating even if the fuel contains

1:26

small amounts of water. The engine must

1:28

keep running under icing prone

1:30

conditions, ensuring reliability

1:32

throughout the full range of fuel flow

1:34

and pressure.

1:36

Each fuel system must be designed and

1:38

arranged to provide independence between

1:40

multiple fuel storage and supply systems

1:43

so that failure of any one component in

1:46

one system will not result in loss of

1:48

fuel storage or supply of another system

1:51

to prevent fire hazards. Fuel systems

1:54

include lightning protection. They are

1:56

built to prevent ignition caused by

1:58

lightning strikes, electrical discharge,

2:00

corona effects, or streamering near fuel

2:03

vents.

2:04

Pilots must be able to accurately

2:06

determine the amount of usable fuel on

2:08

board and receive an uninterrupted

2:10

supply when the system is operated

2:13

correctly. The fuel system must also

2:16

safely isolate or retain fuel during all

2:18

operating conditions and reduce risks to

2:21

occupants during survivable emergency

2:23

landings.

2:25

The fuel storage system includes the

2:27

aircraft's fuel tanks and their

2:29

supporting structure. These tanks are

2:31

built to withstand flight loads and are

2:33

isolated from crew and passenger

2:35

compartments for safety. They are

2:37

protected against heat and environmental

2:39

damage and they store enough fuel to

2:41

ensure safe operation under all expected

2:43

conditions. On larger aircraft, the

2:46

system may also include fuel jettisoning

2:48

which allows excess fuel to be safely

2:51

dumped to reduce landing weight.

2:54

Fuel refilling or recharging systems

2:56

allow fuel to be safely added to the

2:59

aircraft. These systems may use gravity

3:01

fueling or pressure fueling. They are

3:04

designed to prevent incorrect fueling,

3:06

fuel contamination and hazards to ground

3:09

personnel and the aircraft.

3:11

Each aircraft engine is designed to

3:13

operate on a specific type of fuel and

3:16

only the manufacturer approved fuel may

3:18

be used. Mixing fuels is not permitted

3:21

as it can lead to serious engine damage

3:23

or failure. Aviation fuels are broadly

3:26

classified into two main categories.

3:29

Aviation gasoline known as AV gas is

3:32

used in reciprocating piston engines and

3:34

is highly volatile for proper

3:36

combustion. Jet fuel also called turbine

3:39

fuel is used in turbine engines and has

3:41

lower volatility with a higher flash

3:43

point making it safer for high

3:45

temperature operation. Using the correct

3:48

fuel ensures proper engine performance,

3:50

reliability and flight safety. Small

3:53

single engine aircraft use different

3:55

fuel system designs. The layout depends

3:58

on fuel tank location, such as high-wing

4:00

or low-wing aircraft, and how fuel is

4:03

delivered to the engine. Carbbureted

4:05

engines use a different fuel system than

4:07

fuel injected engines.

4:10

The simplest fuel system is the gravity

4:12

feed system, commonly found on small

4:14

high-wing training aircraft. These

4:16

aircraft typically have two fuel tanks,

4:19

one in each wing. Fuel flows by gravity

4:22

from the tanks to the engine without the

4:24

need for a fuel pump.

4:26

The outlets of both tanks are connected

4:28

to a fuel selector valve which allows

4:30

the pilot to select left tank, right

4:33

tank, both tanks or fuel off. When the

4:36

both position is used, fuel from both

4:39

tanks feeds the engine simultaneously.

4:41

Because both tanks can feed the engine

4:43

at the same time, the space above the

4:45

fuel in both tanks must be

4:47

interconnected and vented to the outside

4:49

atmosphere. The vent line usually exits

4:52

on the underside of the wing where fuel

4:54

siphoning is unlikely. After leaving the

4:57

selector valve, fuel flows through the

4:59

main fuel strainer which removes dirt

5:01

and water. From the strainer, fuel flows

5:04

directly to the carburetor inlet. Fuel

5:07

for the engine primer system is also

5:09

taken from the main strainer.

5:12

Low-wing aircraft cannot rely on gravity

5:14

to supply fuel to the engine. So, fuel

5:17

pumps are used to provide the required

5:19

pressure. These systems typically

5:21

include an engine-driven fuel pump and

5:23

an electric fuel pump for backup. The

5:25

fuel selector valve usually allows

5:27

selection of the left tank, right tank,

5:29

or fuel off, but it does not include a

5:31

both position. This prevents the pump

5:34

from drawing air if one tank runs empty.

5:36

After passing through the selector

5:38

valve, fuel flows through the main

5:40

strainer and then to the electric fuel

5:42

pump. The electric pump and engine

5:44

driven pump are installed in parallel,

5:46

allowing either pump to supply fuel

5:48

independently. Before engine start, the

5:51

electric pump is switched on to check

5:53

fuel pressure. After start, it is turned

5:55

off to confirm the engine-driven pump is

5:58

operating. The electric pump is used

6:00

during engine start as a backup in case

6:02

the engine driven pump fails and to

6:04

maintain fuel flow while changing tanks.

6:08

In high-wing aircraft equipped with a

6:10

fuel injection system, such as the

6:12

Teladine Continental system, a portion

6:14

of the fuel is continuously returned to

6:17

the fuel tanks. This returned fuel

6:19

carries fuel vapors with it, helping to

6:21

prevent vapor lock and ensuring smooth

6:24

engine operation. Fuel flows by gravity

6:26

from the wing tanks through front and

6:28

rear feed lines into small accumulator

6:31

or reservoir tanks. From the bottom of

6:34

these reservoirs, fuel is directed to

6:36

the fuel selector valve. The selector

6:38

valve not only routes fuel to the

6:40

engine, but also directs separated fuel

6:43

vapors back into the vent space of the

6:45

selected reservoir tank. An electric

6:47

auxiliary fuel pump then pushes the fuel

6:50

through the strainer and supplies it to

6:52

the engine-driven fuel pump. From there,

6:54

fuel flows to the fuel control unit,

6:57

which precisely meters the amount

6:58

required by the engine. Any excess fuel

7:01

is returned to the pump inlet while

7:03

vapor laden fuel is routed back to the

7:05

tanks maintaining proper pressure and

7:08

preventing fuel vapor formation in the

7:10

system.

7:11

Many small multi-engine aircraft are

7:14

equipped with the RSA fuel injection

7:16

system. Unlike the Teladine Continental

7:19

system, this design does not return

7:21

excess fuel to the tanks. Each wing

7:23

contains two interconnected fuel tanks

7:26

that function as a single fuel source.

7:28

Fuel selector valves allow either engine

7:30

to draw fuel from either wing tank, a

7:33

feature known as crossfeed. From the

7:35

selector valve, fuel passes through a

7:37

fuel filter, then an electric fuel pump,

7:40

followed by an engine-driven pump before

7:43

entering the fuel injection system, and

7:45

finally being delivered to the engine

7:47

cylinders. The system is monitored using

7:49

fuel quantity gauges, fuel pressure

7:51

gauges, and fuel flow indicators. Fuel

7:54

flow is measured by a differential

7:56

pressure gauge and displayed in gallons

7:58

per hour or pounds per hour.

8:01

Large multi-engine aircraft powered by

8:03

reciprocating radial engines such as the

8:05

DC3 are no longer produced, but many are

8:09

still in service. These aircraft

8:11

typically use carbureted engines and

8:13

fuel systems similar to those found in

8:15

smaller aircraft. In the DC3, each

8:18

engine has a selector valve that allows

8:20

fuel to be drawn from either a main or

8:23

auxiliary tank. Fuel flows through a

8:25

strainer to an engine-driven pump and

8:27

then to the carburetor. A cross- feed

8:30

system allows one engine to supply fuel

8:32

to the other if required. Early aircraft

8:35

used a hand operated wobble pump for

8:37

priming, while later models replaced it

8:39

with electric pumps. Fuel pressure is

8:41

monitored through gauges and warning

8:43

lights to alert the crew of any loss in

8:46

pressure.

8:47

Jet transport aircraft use fuel systems

8:50

designed to safely and efficiently

8:52

deliver large quantities of fuel. In

8:54

aircraft such as the Boeing 727, fuel is

8:57

stored in multiple tanks, including

9:00

integral wing tanks and fuselage mounted

9:02

bladder tanks. The wing tanks are built

9:04

into the wing structure itself, while

9:07

fuselage tanks use flexible fuel cells.

9:09

Electric boost pumps in each tank supply

9:12

fuel to the engines and a cross feed

9:14

system allows any tank to supply any

9:17

engine when selected providing

9:19

operational flexibility and redundancy.

9:22

Fueling is accomplished through a single

9:24

point pressure fueling system which

9:26

automatically shuts off to prevent

9:28

overfilling. The same system allows

9:30

controlled defueling when required.

9:33

During flight, fuel may be jettisoned to

9:35

reduce landing weight. Fuel dump systems

9:38

release fuel safely from the wing tips

9:40

while maintaining engine supply and

9:42

proper balance. Dump limit valves ensure

9:45

fuel dumping stops before engine

9:47

operation is affected. We've covered jet

9:49

transport aircraft fuel systems in

9:51

greater detail in an earlier video,

9:54

which you can access using the link

9:55

displayed above.

9:58

Helicopter fuel systems vary in

10:00

complexity depending on the aircraft

10:02

type. Most helicopters use one or two

10:05

fuel tanks located close to the

10:07

aircraft's center of gravity, usually

10:09

near the main rotor mast in the aft

10:11

fuselof. Some tanks are positioned above

10:14

the engine for gravity feed, while

10:16

others rely on pumps and pressure feed

10:18

systems.

10:20

In basic systems, fuel flows from a

10:22

vented tank through a strainer, shutff

10:25

valve, and main filter before reaching

10:27

the carburetor. Light turbine

10:29

helicopters typically use intank

10:31

electric boost pumps that send fuel

10:33

through shutff valves, airframe and

10:35

engine filters, and then to the

10:37

engine-driven fuel pump. These systems

10:39

include vented tanks, electrically

10:41

operated sump drains, fuel pressure

10:44

gauges, and warning switches for filter

10:46

restrictions. Fuel quantity is measured

10:48

using intank fuel probes. Larger

10:51

multi-engine transport helicopters use

10:53

more advanced fuel systems similar to

10:56

those found in jet transport aircraft

10:58

with multiple tanks, crossfeed

11:00

capability, and pressure refueling

11:02

systems.

11:04

In conclusion, aircraft fuel systems

11:07

vary widely depending on aircraft size,

11:09

configuration, and engine type. However,

11:12

all fuel systems share the same goal to

11:15

deliver clean fuel at the correct

11:17

pressure reliably and safely under all

11:20

operating conditions. Understanding fuel

11:23

systems is essential for safe aircraft

11:25

operation and maintenance. Thank you for

11:28

watching.

11:33

[Music]

#Jobs & Education