“How can all the diversity and, sort of, seeming order that's out there in the world emerge from a process dependent upon chance?”

Show More Show Less View Video Transcript

0:00

How can all the diversity and sort of seeming order that's out there in the world

0:03

emerge from a process dependent upon chance? It kind of works like a staircase

0:10

Chance invents and natural selection propagates that chance invention. Our immune system works on the very same principles of mutation and selection

0:20

as evolution at large does in the big world. Cancer is truly an evolutionary disease

0:29

meaning that it is a disease that results from the exact same evolutionary process we're describing

0:35

So while Darwin's is the most famous figure associated with the theory of evolution

0:39

Alfred Russell Wallace played a key part. And in their day, this was referred to as the Darwin-Wallace theory

0:47

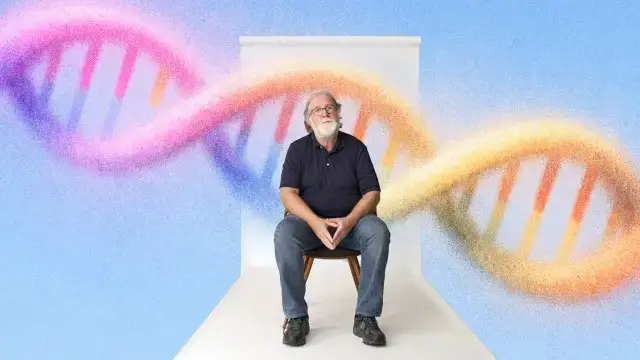

I'm Sean B. Carroll, evolutionary biologist and author of several books, including my most recent series of fortunate events

0:54

Chance and the Making of Planet, Life, and You. Chapter 1. How Life Works, The Staircase of Evolution

1:09

So evolution, what it really means is change over time. So we want to know how that change occurs over time

1:16

And there's two dimensions to this process. And it kind of works like a staircase

1:21

And one process is mutation. And that's the rise in the staircase

1:26

those occur by chance. If mutation didn't happen, all things would be identical. So you need mutation

1:32

to make individuals different from one another. Those mutations are genetic changes, changes in

1:37

their DNA. If by chance that changes a property that favors reproduction, survival of the individuals

1:45

it will spread. And that's the selection process. And that's sort of the run in the staircase

1:50

chance invents and natural selection propagates that chance invention. And once that process has

1:57

happened, new mutations can then be added on top of that, maybe even changing the character a little

2:03

bit further. And that's another rise in the staircase. And if that's working better, that's

2:08

going to spread. And so it's the cumulative set of mutations and the cumulative process of selection

2:14

that takes us up that staircase. So that staircase could have goodness knows how many stairs

2:19

but it has to go through this stepwise process of individual mutations arising

2:26

sweeping through the population, new ones arising, sweeping through the populations. It doesn't go from the base of the stairs to the top of the stairs in one jump

2:34

And this is hard for people to get their heads around because they may think about that first step. And it's sort of hard to imagine, you know, how do you get something as complicated

2:41

you know, as individual organs like an eye or a wing of a bird or things like that

2:46

But time, immense time, the speed with which some new adaptation spreads through a population

2:54

depends upon the magnitude of the advantage it conveys. If it's about a 3% advantage, meaning that about 103 individuals survive for every 100

3:04

that don't have it, well, that will take about 1,000 generations to spread through the population

3:09

Now, I'm saying generations because it depends upon the generation time of the creature. So if the generation time, for example, if humans is 25 years, it'll take 25,000 years

3:18

for that to spread through the human population. But if the generation time is 20 minutes, you can work it out

3:23

It'll take 20,000 minutes to spread through, which is much shorter. It's a matter of generations because its reproduction is a generation by generation process

3:34

It's really important to underscore that these mutations occur at random, without any consideration

3:40

of whether they're good or bad for the organism. It's the external conditions that are going to sort this out

3:46

So some things can be good for one creature and bad for another

3:50

So, for example, a color change might make a creature more invisible in some settings, more visible in another

3:58

Some mutation may make it better adapted to warmer climates, less well adapted to colder climates

4:05

So it depends on these external circumstances. So the mutations arise at random

4:10

Well, what about those external circumstances? Well, we'd say the abiotic conditions

4:15

whether the physical world that the creature is living in. Well, that's also generated a lot at random

4:21

Tectonic plates moving across the earth, you know, volcanism, all the things that shape the conditions of life

4:28

are often due to physical processes of the earth. Of all the many thousands and millions of things

4:35

that creatures have come up with, I have a few of my favorites that I think really exemplify this process of adaptation

4:42

And one of my favorite sets of creatures are some fish called ice fish. They live in the Southern Ocean around the Antarctic

4:49

And they live in water that is actually below the freezing temperature of fresh water

4:55

They're right around about 29 degrees Fahrenheit is the ocean around the Antarctic

5:00

And that's a challenging environment. So challenging, for example, that you may know that there's ice flows around there

5:08

And if little ice crystals just get into the bodies of these fish, they'll nucleate freezing

5:14

They'll freeze like fish sticks. So they need to have a mechanism that prevents them from freezing at that cold temperature

5:23

And what they've done is they've evolved antifreeze. Certain proteins in their bloodstream, made in very large quantities

5:30

suppress the ability of ice crystals to grow inside their bodies. And so they're able to

5:36

tolerate that sub-freezing water of the Antarctic. And other fish aren't. So what's happened over the

5:42

last 30 or 40 million years is that a lot of fish that once swam in those oceans, sharks and rays

5:47

and all that, they're all gone. They're extinct from those waters. We find them in more temperate

5:51

waters. But it's the ice fish and the antifreeze-bearing relatives that exploit those waters

5:58

And the ice fish have also come up with something that's incredibly nifty and shocked naturalists when they first discovered it

6:05

Which is, if you open, which any fish you know, slice it open

6:09

you're going to see red blood because that's something that animals with backbones have

6:12

and have had for almost 500 million years on this planet. But you slice open an ice fish, their blood is colorless

6:19

because they've gotten rid of red blood cells. So they don't even have a mechanism for carrying oxygen actively in their bloodstream like we do

6:28

They've ditched red blood cells. And the reason they've ditched red blood cells is at those low temperatures, it makes their

6:34

blood too viscous. And that's a disadvantage. To the ice fish, it was an advantage to get rid of red blood cells

6:43

To the rest of us, it's instantly fatal. So it's a good illustration of just how conditional these adaptations are, that to exploit the

6:51

resources of the Southern Ocean, you've got to make antifreeze and get rid of your red

6:55

blood cells, where the other parts of the world antifreeze would be irrelevant and your red blood

7:00

cells are necessary for every second of life. Let's talk about speciation. That process of

7:07

variations, helping to adapt, that's the process of adaptation. But speciation is the generation

7:13

of two species from one. What does that take for there to be two species to form

7:20

And we know, this is where the island biology of Wallace and Darwin help, is that they were seeing

7:24

species on different islands Well islands provide some isolation and that isolation means that those populations aren exchanging genes Over time each of those populations will

7:38

accumulate mutations that exist in one population and not the other, vice versa. Well, those can

7:45

become genetically distinct enough that if those things were ever to come back again in contact

7:50

They may not be compatible with one another, and they'll be species

7:54

So how long does that take? Well, it's been estimated for big animals like mammals and birds

8:00

that works out to roughly be about two million years. But two million years is still a long time

8:06

And you've probably heard, for example, that there's now very strong evidence

8:10

that Homo sapiens, our species, mated with Neanderthals, a distinct species. And what's really happened in the last few decades is that for biologists, that species barrier has become much more porous than we first thought it was

8:26

In the old days, in Darwin's days, species were characterized as really distinct things, and we didn't think there was any kind of shenanigans going on between them

8:34

But we now understand that it's a much more porous situation, that for some period of time, as populations are diverging, they can get back together

8:42

and things that we humans might call distinct species can often interbreed

8:48

Another common question or idea is that, you know, for example, if humans evolved from apes, why are apes still around

8:54

Well, the important thing is to understand that evolution is a splitting process. So the family trees keep splitting

8:59

So the human part of that tree has had now its own separate history from the ape part of that tree

9:05

We shared a common ancestor about 6 million years ago. But apes have gone on living as they do, for example, in the old world

9:14

And there's a great diversity of apes, of course, still here, baboons, orangutans, gorillas

9:19

chimpanzees, et cetera, while the human branch has gone on and has its own evolutionary trajectory

9:26

It's not that evolution is linear and that everything new replaces the old

9:30

It's a splitting process. And so that's why the tree of life has just split into enormous numbers of branches

9:38

from common ancestors. Two of our main records of evolution are the fossil record and the DNA

9:45

record. The DNA record is largely only accessible to us for living creatures and maybe some creatures

9:51

that have lived over the past million years. You know, do we have every brick? Do we have every

9:56

intermediate? No, because, you know, extinction takes away 99.9% of all species. So if there was

10:02

no extinction, we'd have a perfect record of evolution, right? We don't have the DNA record

10:06

of dinosaurs, for example, but we've got the fossil record of dinosaurs. So we use these two

10:11

records to sort of reconstruct the history of life. That allows us to reconstruct the evolution

10:15

of things that are fairly complex. Let's take something like a walking limb from a fish fin

10:22

This evolutionary process transpired over 20, 30 million years, about 380, 390 million years ago

10:30

To do that, we have to get fossils that represent the various stages of evolution and see how did

10:36

all the bones change so you went from a swimming fin to a walking limb. And the fossil record by now

10:42

is pretty darn good. Then we can go to creatures that have fins, fish, and we go to creatures like

10:49

amphibians that have limbs, and we can figure out how do those genetic programs work and where are

10:55

the differences. Now we don't have every detail sorted out, and that would be incredibly time

11:01

consuming and expensive to do. But we certainly have the general picture that we understand how

11:09

the bones changed in history, and we understand how the development program changed to generate

11:15

a limb in the place of a fin. And that's not something Darwin ever had. That's something that

11:21

we really only had for the last 20 to 25 years. So evolutionary science keeps building on this

11:27

huge foundation. And what we get is an ever more detailed and ever more confident record of what's

11:33

happened. But what's it no doubt is that this process, mutation and selection, mutation and

11:39

selection, is the universal going on in every population of every living thing every day

11:46

In fact, this process of mutation and selection seems so universal that we think it must have

11:52

played a vital role at the origin of life. And that anywhere where life exists in the universe

11:57

it's operating. So evolution is this vast and rich process. And we've been trying to understand it

12:03

for 160 years. And in the course of that, there's some misunderstanding in just how it's communicated

12:08

where I think there's some conflict between the terms we scientists use and sort of their

12:12

common understanding. And one of those is theory. We talk of scientific theories. Theory is much

12:20

higher in the hierarchy than, for example, a fact or just an observation. A theory is assembled from

12:27

lots and lots of facts and independent lines of evidence that sort of cohere. So a theory is

12:33

really sort of the top category of scientific idea. Of course, you know, in the street, theory

12:39

might mean that's my best guess, or that's just something that I'm conjecturing. The way we talk

12:44

about those kind of conjectures, we call those hypotheses. And then when hypotheses have been

12:49

rigorously tested, that's what can contribute to making a theory. So folks, when we speak of theory

12:57

think that we're still very tentative about, you know, the truth of evolution. That's not all the

13:04

case. The theory of evolution, which has grown enormously in the last 160 years, is a huge body

13:13

of observations, evidence, and facts that are consistent with one another, that come from

13:17

completely different sources of science. And that's what gives it its power. We, of course

13:24

wish that maybe that connotation of theory that's more of the everyday connotation would

13:31

be better understood. Chapter two, how our bodies work, the staircase of self-defense

13:43

Now, here's something about the staircase of evolution that's very little appreciated

13:49

It's going on in every one of our bodies every day. It's keeping us alive

13:57

And that's because our immune system works on the very same principles of mutation and selection

14:03

as evolution writ large does in the big world. Every day, we are exposed to all sorts of potential pathogens

14:13

Bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites. We've got to fend these off. And by the time we're full-grown adults

14:22

there are actually more bacterial cells living on and in our bodies

14:27

than there are our own cells. Trillions and trillions of microbes. We've got to keep these in check

14:34

or, of course, will suffer and potentially die. And that's the job of our immune system

14:41

And our immune system operates on the very same principles as the staircase of evolution

14:47

It's a staircase of self-defense. And the most remarkable property of our immune system

14:52

is it seems to be able to recognize as foreign virtually anything that can come at us out of nature including entirely new pathogens that didn even exist in the human population And how do we do that Well it involves a process

15:08

based on mutation and selection. And the way this starts, I'll just describe it starting with a

15:13

single cell. So you have billions of cells, but these cells have different molecules on their

15:19

surface that when they are complementary to molecules on the surface of a pathogen

15:24

they're activated. They're engaged. And when engaged, they multiply very rapidly such that

15:32

over a period of about a week, one cell may become billions of cells and start to pump out

15:37

large quantities of chemical weapons known as antibodies that thwart that invader. These

15:44

billions of cells of our immune system are actually clones. Clones that are subtly distinct

15:50

from each other that have unique ability to recognize something else. Now that something else

15:56

could be any variety of things on an invading pathogen. But once they recognize that, that clone

16:03

gets amplified, can grow to be many, many, many cells in the course of a week or so

16:09

That first wave of defense is decent, but not optimized. There's actually a mechanism

16:16

to make those chemical weapons, the antibodies that cell makes, even more potent, even more deadly to essentially the invading pathogen

16:26

And that's because there's a specific genetic mechanism that mutates the antibody encoding genes

16:33

leaves the rest of the genes in the body alone. Just the antibody genes start undergoing a process called hypermutation

16:39

and therefore generating all sorts of antibody variants. and the antibody variants that recognize the pathogen better are selected for

16:49

So here we go. We're climbing the staircase. So this hypermutation process, you now select antibodies

16:55

And this can go through various cycles to make ever better and better antibodies

16:59

So we're really zeroing in on this particular pathogen. So late in immune response, say, for example, the second week you're recovering from a flu virus

17:09

your immune system is ever more potent, ever more powerful in defeating its enemy

17:18

because it's up that staircase. Eventually, a staircase sort of splits. And some cells are set aside, so it's called memory cells

17:28

They're there to be used when this pathogen is encountered again. Other cells continue to make the antibodies

17:35

Now, this is the marvelous thing. Y'all are familiar with a phenomenon where, for example, you don't get measles twice

17:42

you don't get chicken pox twice, etc. Why is this? Immunological memory

17:49

That even if 50, 60, whatever number of years ago, you might have been exposed to that virus

17:53

your immune system is still poised to attack it again if you're exposed again

18:01

so you don't even get the infection. This system is called adaptive immunity

18:08

much like the process of evolution of mutation and selection is adaptive

18:13

It really only exists in this form in animals with backbones, long-lived, generally larger animals

18:20

And you can see its utility because the longer your lifespan, the greater the chance you're going to re-encounter a particular pathogen

18:28

If you're a short-lived mayfly or something like this, You don't live long enough to see the same thing twice

18:34

There's not that kind of immunity. So lots of animals, including simpler things like worms and flies and all that, they have

18:42

what we call innate immunity. They have ways that sort of put barriers up against pathogens

18:48

But this adaptive immunity only exists in creatures with backbones, with vertebrates

18:53

And it's pretty elaborate in us, in mammals, animals with fur, et cetera

18:59

but it's pretty well developed even in things like fish and sharks. Inside our bodies, the time scale of this process is very, very fast

19:06

It's more like what we described with respect to microbes because it starts with cells and cells that can multiply pretty frequently

19:13

So a lot of evolution can take place in a short time. Most of us are sort of familiar that most infections don't knock us down for more than about a week

19:22

That's when our immune system eventually sort of catches up and overtakes the pathogen

19:25

So that gives you a sense of the timescale it takes to mount the response, expand that response to the point where it overwhelms the pathogen

19:33

Whereas out there in the world, sort of a battle between predator and prey or whatever, that may go on for hundreds of thousands of years before there's sort of a winner

19:41

Same process, much more rapid timescale in your body. How is it possible that we can recognize virtually anything that the world will throw at us

19:51

And fundamentally, one of the problems there is sort of a coding problem. how can one make all the different kinds of antibodies that could recognize all the different possible pathogens that, you know, a species might encounter

20:04

And the solution to that required understanding how antibody genes are encoded in DNA

20:12

something we weren't able to do until the 1970s or so. And what that's revealed is that we mix and match pieces of antibodies in a way that we can generate millions of combinations of antibodies

20:28

And it's now estimated that we may be able to make about 10 billion different antibodies

20:35

And you might go, well, that sounds sort of impressive, but okay. Well, here's the thing

20:39

In our entire genome, all of our DNA, we only have about 20,000 genes

20:46

So how do you make 10 billion antibodies when there's only 20,000 genes to begin with

20:53

And this is the brilliant trick of the immune system. It makes antibodies from short little gene segments that it mixes and matches in millions

21:04

if not billions, of combinations. So the trick of combinations is that it's just like if you can take a deck of cards

21:13

right? And you have five cards you draw from a deck. There's lots and lots of different combinations

21:19

you can, even if you have only 52 different cards. And so from a modest number of antibody genes on

21:24

the order of a few hundred, by mixing and matching them in pieces, we can generate enormous numbers

21:30

of antibodies. So the immune system, even with all its powers, can still be sort of beat to the punch

21:37

There's still pathogens that can kill us. And this is why we vaccinate. And we understand

21:42

And in vaccines, generally what we're giving is a little component, usually a non-living component

21:50

not the virus itself, not the pathogen itself, but maybe just a molecule that represents that pathogen

21:57

And we're using that to prime the immune system. So we're activating the immune system

22:02

So it goes through some of those steps on the staircase, establishes memory

22:07

and is poised to respond should we encounter that pathogen. And by being vaccinated, by being immunized, that can save lives, certainly save the suffering

22:22

of any particular disease shorten its course save us days off work whatever it might be But this is why we have these vaccine strategies and we seek ways to give our immune system a head start

22:36

Because if we don't vaccinate, then we're at risk of suffering the damage that pathogen causes

22:43

unless or until our immune system catches up, feeling lousy, or in some cases there's lots of morbidity with these infections

22:52

One of the most notorious ones in human history is the smallpox virus, which killed hundreds

22:57

of millions of people in human history and even tens of millions of people in the 20th

23:01

century until we came up with a vaccine. And there was a global effort to vaccinate virtually every human on the planet

23:10

And that eradicated smallpox from the world so that now we don't even vaccinate for smallpox

23:16

But that was a virus that moved faster and caused greater pathology than our bodies could keep up with

23:32

So we understand this evolutionary process is what drives our adaptive immune system and protects us against enemies from without

23:43

But it turns out that sometimes the enemy is coming from within the house

23:49

And I'm speaking specifically of cancer. And cancer is truly an evolutionary disease

23:55

meaning that it is a disease that results from the exact same evolutionary process we're describing

24:00

of the evolutionary process in the external world, of the evolutionary process in the immune system

24:07

Cancer forms in the same way. And that is mutations take place in individual cells that if they convey some growth advantage to those cells, those cells may outgrow their neighbors and additional mutations may happen

24:24

So they outgrow their neighbors further. And that's what we define as a tumor, a population of cells that is now growing unregulated relative to its normal neighbors

24:35

And that's a threat because that unregulated growth can lead to spread throughout the body

24:40

can lead to organ involvement, et cetera, and death. But the other concern is, as that cancer gets larger, some of those cells are going to get

24:48

yet additional mutations. And some of those cells are going to get yet additional mutations

24:54

And so as cancer progresses over time, that tumor is less and less like the cell it started

25:02

from and the tumor itself is more genetically diverse. And that's giving us a real challenge

25:09

therapeutically. So there is a staircase of cancer. And the way to understand that is that

25:16

our risk of cancer is really age dependent. The incidence of cancer goes up really significantly

25:22

as we get older. And think for a moment why that might be. And what that is, is it takes time to

25:29

climb that whole staircase. So later in life, individual cells have gone through more divisions

25:35

They've had more chances to accumulate mutations, mutations that give them some growth advantage

25:39

over other cells. And so our risk of cancer grows really significantly as we get into our 40s, 50s

25:45

60s, and 70s. So that tells us, not only is it an evolutionary disease, it's a genetic disease

25:54

It's mutations taking place in genes that somehow disrupt the normal process of controlling

25:58

cell growth. So a huge interest has been, what are those genes? How do we find them? How does

26:04

this all work? We first got a hint that cancer was a genetic phenomenon when scientists first

26:11

started seeing chromosomal changes in cancers, chromosomes that were broken and fused and things

26:16

like this, and that all the tumor cells would have those broken chromosomes or tumors that

26:21

rose independently in different people would have those rearranged chromosomes. And that gave us a

26:26

okay, something genetically is going on. But the crucial thing was to identify, well, what genes

26:32

Well, thanks to genomics, thanks to gene cloning, we now know that there are about 20,000 genes

26:39

that essentially run the human body. And we've identified about 150 of those

26:44

that when mutated can contribute in some way to cancer. We'll call those drivers

26:50

And those drivers split into two classes. One class we'll call accelerators because when they're mutated, they really accelerate

27:00

cell multiplication. They also have the name oncogenes, promoting cancer. Another class of genes, they serve as brakes

27:08

They hold back proliferation. But if they're disrupted by mutation, then we no longer have their braking function

27:15

and the cells can grow out of control. So just like an out of control car, out of control cell proliferation can be due to a

27:23

accelerator or broken brake. It can be due to oncogenes that promote cancer or tumor suppressors

27:31

would normally suppress that cancer, but they've been disrupted by mutation. So scientists have

27:37

banded together across the world to build this sort of catalog of driver genes. And so they

27:43

study the state of these genes and all sorts of cancers. And there's some really, really clear

27:48

insights from doing this. And the first is, well, it's a multi-hit process. Usually any cancer has

27:56

disruptions to multiple genes, might be three, four, five, even seven of these driver genes

28:02

And if we look at cancers that arise in kids and compare that with cancers that arise in adults

28:09

there's a really profound distinction. When we look in kids, we see there are very few mutations

28:14

overall in the DNA of the cancer cell, but they'll be in driver genes. And you don't see many other

28:20

mutations that have taken place that are different, say, from mom and dad's DNA. And that's because

28:26

a young child, its cells have not gone through that many divisions. It's not accumulated very

28:31

many other mutations. It just so happens the mutations that occurred were in these critical

28:35

driver genes. It's horrible, heartbreaking, bad luck. But the longer we live, all of our cells

28:44

whenever DNA is copied, mutations occur. Now, most of those mutations have no effect. They're

28:51

sprinkled among the billions of bases that we have. But every now and then, one of these driver

28:56

genes gets hit. Well, the longer we live and the more divisions our cells have gone through

29:01

the greater the chance that there have accumulated mutations and eventually hit one or more driver

29:07

genes. And once they hit a driver gene, if that cell starts to outproliferate its neighbors

29:13

well then those cells in turn may be going through more rounds of division, more mutations

29:20

And so now essentially the snowball is rolling such that by later in life, we have cells that

29:27

have accumulated a number of driver mutations. And many of our cells at least have one driver

29:33

mutation. It may not be pathogenic whatsoever, but a lot of our cells will have mutations in them

29:39

some of which could eventually be a problem. So understanding that cancer is this sort of disease

29:45

this interplay of mutation and selection, there's really three factors that can contribute to the

29:50

formation of cancer. First is just bad luck, that the small number of mutations that are going to

29:55

happen anyway, just happened to hit driver genes. Really, that's the explanation

29:59

The act for cancer and the kindest thing you can do to any parent whose child is struck

30:04

is to reassure them that there was nothing they did to cause it and nothing they could

30:08

have done to prevent it. Then there are lifestyle issues like tobacco use and sun exposure

30:15

They'll increase the risk of particular cancers, lungs, because that's where the smoke goes

30:20

And of course, the skin, because that's what's being exposed to the sunlight

30:24

And the third is just age. It's time. The longer we live, the more divisions our cells have gone through, the more mutations have happened

30:32

and the more all the environmental things that we've been exposed to have had a chance to work on us

30:36

So that later in life, our cells are carrying lots of mutations, and we just hope that none of those cells have sort of that unlucky combination of mutations

30:44

that will make it an uncontrollable tumor. So I think there's a few pillars of how we're combating cancer now

30:52

that's really different from how we did it before. Now, for prevention, we're looking for these mutations. So you've seen, for example, a product

31:02

like Coligard where a stool sample can be sent to a company. Well, they're looking for mutations

31:07

characteristic of gastrointestinal cancers in that fecal sample. Okay, so that's early detection

31:14

And we know that the earlier you can detect cancer, the better shot you have of counteracting it

31:19

The second pillar is to know those cancers and to realize that different driver genes are mutated in different cancers

31:27

So instead of treating breast cancer as a monolith, we now subtype breast cancer according to the mutations that exist in an individual's tumor

31:37

So it's really important that the genotype, meaning the genetic makeup of a tumor, is yzed when that is first diagnosed

31:46

that will shape the treatment course. Because the other thing that oncologists are doing

31:52

is they use different drugs, different regimens to go after these cancers

31:57

is to study which things work against which genotypes of cancer. So we're now, I think

32:06

classifying and categorizing cancers with much greater degree of sophistication. And then there is the specific therapy side

32:14

All sorts of drugs have been designed to go after those mutated genes

32:22

So to specifically target what has gone wrong in an individual cancer

32:27

because of the mutation of a particular gene. Some of these drugs have been spectacular success

32:34

Some are doing a good job at, let's just say, buying time

32:37

in the hope that the cancer can be contained and managed over the longer period of time

32:43

and treated more as like a chronic disease, not necessarily eliminated, but at least managed. Only in the last about 25 years has this really

32:51

been possible, but the practice of this has really grown enormously in the last about 15 years

32:58

And there's all sorts of new drugs under clinical trials at any given moment. Again, trying to give

33:03

a much more specific therapy to the particular alterations that have happened in a given

33:09

individuals' tumors. Better prevention, better diagnosis, better therapy. This is driving cancer

33:18

rates down, certainly for certain types of cancers, and hopefully going to drive survival

33:24

rates up over the long term. These parallels in how life evolves, how the immune system works

33:34

how cancer arises, at one level they're startling because the connections aren't so obvious

33:41

but fundamentally they're operating on the same process, this mutation and selection

33:47

But of course, mutation is a random process. And it's really hard to get our heads around

33:53

how can all the diversity and sort of seeming order that's out there in the world

33:57

emerge from a process dependent upon chance. Yet, there you have it. Whenever you have

34:07

variation and you have competition, natural selection operates and gives us the variety of

34:15

life. In the immune system, chance is being exploited. You think, well, we can't leave the

34:20

defense of our bodies against chance, but here we're exploiting chance. Now, of course, cancer

34:27

has its root in chance, the unlucky mutation that hits a gene that could throw a cell out of balance

34:33

with the body. That evolutionary process we've been discussing is one of error and trial

34:40

Whereas humans sort of think like engineers, that we think of what we want as an outcome and

34:46

how we can get there sort of in the shortest distance. And we may use some trial and error

34:51

but we really try to minimize the error. Whereas really these evolutionary processes start with

34:57

error. They start with a random change and then try those things out. And I think it's just been

35:03

hard for us to get our heads around that. Yet, the more we understand this and all of its

35:08

manifestations and the immune system and cancer are two later realizations, we see that this process is a fundamental biological process, random genetic variation

35:22

and the sorting of that variation through natural selection. Chapter 4, The Untold Story of Alfred Russell Wallace

35:35

So, about 15 years ago on a visit to the University of Cambridge

35:42

I happened to visit the archives there, where they hold a lot of original materials from Darwin

35:48

And to my astonishment, they brought out and placed into these sweaty hands

35:54

a copy of one of the early manuscripts that many, many, many years later would be modified

36:00

into the origin of species After Darwin got back from his voyage he was pondering these ideas and he decided to write them down in essay form And by 1844 he completed a 230 essay that fleshed out a lot of his basic ideas

36:16

He wouldn't publish anything on evolution for 15 years. That essay, I think, was lost for decades

36:22

and found under the steps of his house. So when it was presented to me, all over the manuscript

36:29

including on the back pages, there were drawings by Darwin's kids. They had been using it like

36:34

scrap paper. It was a spine-tingling moment for me because this was really the birth of one of

36:40

the biggest ideas humans have ever had, and I'm grateful that they found it under the stairway

36:46

at Darwin's house. So while Darwin's is the most famous figure associated with the theory of

36:52

evolution, Alfred Russell Wallace played a key part and deserves huge credit both for his ideas

36:59

and for his enormous effort. So really important to understand that the prevailing idea at the time

37:04

to which Darwin subscribed and most British scientists subscribed was what we'll call special

37:09

creation or the theory of special creation. And that was the idea that every species was

37:14

specially created by God and sort of placed or at least emerged in the habitat or in the place

37:21

on the globe that best suited it. Now, what started to shake that theory in Darwin's mind

37:28

and in Wallace's mind was in the course of their journeys, particularly when they visited

37:33

archipelagos, strings of islands. Each of them observed species on different islands that were

37:39

slightly different from one another. Now, Darwin, this is just a twist of his story. After nearly

37:45

five years at sea and having made a full voyage around the world, they were about to turn

37:50

from the southern tip of Africa back up to Europe. But his captain, who was sort of obsessive

37:58

decided he wanted to do some more measurements in South America, so he went back across the Atlantic

38:02

And Darwin was, at first, just crestfallen that he wasn't headed home

38:07

But he needed to make good use of that time, and he started to take his notebooks out

38:11

and review what he had seen, but also sort of annotate them

38:16

And he thought back to the Galapagos Islands, and he thought back to these mockingbirds that he had seen on different islands

38:23

And he saw that on different islands, the mockingbirds were slightly different from one another

38:27

in their feather patterns and things like that. And he thought these islands were within sight of one another

38:32

just 50 or 60 miles away from one another. If a creator was placing species sort of perfectly adapted to each place

38:41

why would these mockingbirds be just slightly different from one another? Now, Wallace's story is more dramatic because Wallace, after four years in the Amazon

38:52

really at the breaking point, decided to return to England with specimens and whatever ideas he had collected

39:01

And on his way home, his ship caught fire. He had to get into a lifeboat

39:09

The ship sank right in front of him with all of his specimens. and he was in an open lifeboat for 10 days hoping to be picked up

39:16

And he was picked up, eventually made his way back to England. You'd think after that experience he would have sworn off all voyaging

39:24

But two years later he goes back out and does an eight-year voyage across the Malay Archipelago

39:29

and collects tens of thousands of more specimens. He noticed, for example, the bird-winged butterflies

39:36

These beautiful, incredibly brilliantly colored large butterflies were slightly different from island to island

39:42

They both thought in the theory of special creation, these islands all looked alike

39:47

Why would there be just slightly different species island to island? And it struck both of them because species could change

39:55

Species weren't stable. They weren't immutable, as the theory of special creation argued

40:01

They, in fact, changed. And this opened up the big question then

40:05

or at least the daring question of, are species the product of natural processes or divinely created

40:15

And they thought this was strong evidence that species change naturally. They change according to the conditions they encounter in different places

40:24

And the islands were crucial sort of laboratories for understanding this because the volcanic islands of the Galapagos look very similar to one another

40:32

but the creatures were a bit different. The islands of the Mali archipelago, very similar foliage and all that, but the creatures

40:38

were a little bit different. And the only way they could sort of reconcile that was to say, well, the species were changing

40:44

They weren't fixed. They weren't immutable. And as they worked further, they thought about some other patterns

40:51

They knew about fossils. In fact, Darwin discovered some really interesting fossils on the coast of Argentina

40:57

And through correspondence back home, while he was at sea, he realized these were sort

41:03

of larger versions of animals that lived in South America at the time. So he found, for example

41:07

giant ground sloths, you know, huge, like eight feet tall ground sloths, much larger than the

41:13

living ones. But he realized, hmm, those are extinct creatures. What's the relationship between

41:20

the extinct and the living? He's starting to think about that genealogy between the extinct

41:25

and the living. And Wallace is also becoming aware of these fossils because he's reading now what's

41:30

coming out from the first studies of fossils in Britain in the first part of the 19th century

41:36

They had also each read this work by an economist, Thomas Malthus

41:43

And Malthus emphasized that there were limits on populations. He thought about the growth of populations

41:50

And Malthus said that, you know, disease and famine, that limited, for example, the growth of populations

41:57

Well, Darwin and Wallace, being out of nature, they understood that life was very tough

42:02

They understood that really life was a battlefield, a contest, and that far more young are produced

42:10

than can survive to adulthood And what uncanny is when you look at the writings of each of these individuals Darwin notebooks Wallace draft manuscript they use the same language

42:22

They describe life as, quote, a struggle for existence. Exactly the same words, unbeknownst to each other

42:30

And they talk about variations, however slight, and that they could be favored

42:36

And that led Darwin to coin the word natural selection. they'll be selected for in nature. And the things that are disadvantaged will be selected against

42:49

And Wallace said essentially the same thing, that one could imagine if there's a slight advantage

42:54

that slight advantage will be passed on generation after generation. So Darwin for 20 years is back

43:03

home in England. He's well known because right after he did the voyage on the Beagle, he wrote

43:08

the book that we call today The Voyage of the Beagle. And it was a popular read. It's a great

43:13

read. It's still a great read today about his travels. And he was an eminent naturalist

43:19

Wallace was an unknown. He was from far more modest upbringing, and he was really paying his

43:25

way on his voyages by selling a fraction of the specimens that he was collecting. So he was

43:30

thousands and thousands of miles away from the center of science in England, and he wasn't

43:35

connected really at all. So Wallace, by 1858, has a pretty good idea that life changes, life evolves

43:47

And he writes up a very short account of his thinking about how that works. And he decides

43:54

to send it to the one naturalist with whom he struck up a correspondence who thinks might

43:58

appreciate it. He sends it to Charles Darwin. Well, this event rocks Darwin because Darwin has

44:04

not gone public with his theory of evolution. And now here's this faraway correspondent, 7,000 miles

44:11

away from England, who in just a few pages has essentially the same idea that Darwin has, that

44:16

Darwin's labored on for about 20 years. Well, Darwin's friends rally and decide that the best

44:21

thing to do would be to read Wallace's paper and an excerpt from Darwin's work in front of a British

44:28

Scientific Society to sort of put both of these ideas out in the public. Darwin wasn't there. It

44:35

turns out Darwin had suffered tragedy. He was burying his Charles Jr., one of his sons, on the

44:41

day this paper was read. And Wallace was 7,000 miles away, didn't even know what was going on

44:46

It really didn't make much of a splash. Not much attention was paid. But the next year is when

44:53

Darwin published on The Origin of Species, and that's when everyone paid attention

44:57

The response and acceptance or rejection, particularly to Darwin's Origin of Species

45:04

because that's the book everybody could put their hands on. It sold out in its first printing

45:09

It was reprinted quickly. It was translated into other languages. American versions were made

45:14

So people who are interested in science, biology, natural history around the world

45:18

could get their hands on Darwin's ideas. So their reactions were a very wide spectrum

45:26

Thomas Huxley, who was one of Darwin's close confidants, sort of thought, you know, wow

45:31

why didn't I think of that? He thought it was, you know, compelling and sort of obvious

45:37

But I think one thing to appreciate with Darwin is that his book is extraordinary in that

45:42

he also presents and yzes the critiques of his own theory. I mean, imagine that

45:49

This is just something that human beings don't generally do. If they've got an idea, they're going to put out all the evidence in favor of their idea

45:55

And they're usually not going to present to the opposition all the evidence, either against it or all the evidence that's missing

46:02

But Darwin did this in a masterful way and basically often saying things like, you know, if something, if a particular thing was found, it could crush my theory

46:10

Or if my theory is true, this would be true. But there wouldn't necessarily be any evidence weighing on that

46:16

So it was a masterful presentation. And I think that made it very accessible to people

46:23

They understood the strengths and weaknesses of the theory. And then new discoveries could be interpreted in light of that theory

46:30

And as some new discoveries, particularly from the fossil record, came to light

46:34

well, that gave a lot of power to Darwin. Because Darwin at the time Origin of Species was published

46:40

the fossil record was pretty skimpy. But Darwin made some really strong predictions about what should be found

46:46

for example, in the fossil record. And one of those was transitional forms

46:50

if the tree of life has evolved in the way that he said

46:56

there should be forms that are intermediate between existing forms today. And two years after the origin of species, a fossil called Archaeopteryx

47:05

which has got mixed characteristics of both birds and reptiles, was discovered

47:10

And I mean, you couldn't have drawn anything better than that fossil for supporting Darwin's theory

47:18

So I think the reception of the scientific community, some of it at first was positive, but there were long, long holdouts

47:28

There were career-long holdouts against Darwin among even very eminent natural historians, biologists, and scientists

47:37

And that holdout was really for reasons we'd all recognize today. While Darwin didn't, in 1859, didn't comment directly on the evolution of humans

47:48

he did later in 1871. Everyone knew that humans were going to be a touchy subject

47:54

because for at least a couple millennia, the thinking was that man was created in God's image

48:03

not descended from some previous animal forms. But clearly Darwin's theory would be interpreted to say that

48:10

No, humans, just like every other animal, evolved their anatomy and their physiology

48:16

from pre-existing forms. And some scientists held out on that point both perhaps from their own viewpoint of faith but also I think because of some pressures in the academy Darwin was on the short list to be knighted When the origin of species came out

48:34

well, he never got that knighthood. So, you know, this was an idea that many people found repulsive

48:41

They were really worried about the societal implications to sort of take the creator out

48:46

of the immediate picture of sort of, you know, tending to human affairs. And that's, of course

48:54

still a struggle that exists to today. And, you know, scientists, you know, being part of society

49:00

it was not universally, you know, accepted, far from it. Where Wallace really finally grasped the

49:08

scope of what Darwin had been working and thinking was in 1859, when The Origin of Species was

49:16

published. And he received a copy of The Origin of Species. And he read it and re-read it. In fact

49:26

Wallace's own copy is in the Natural History Museum in London, so we can understand sort of

49:30

his reactions in real time. But I think one of the most poignant things I know in the history of

49:35

science was Wallace's put his thoughts and reactions in a letter to his close friend and

49:41

confidant, Henry Walter Bates, with whom he had first traveled to the Amazon. on. And Wallace is just gushing with admiration for Darwin. And he says, I never, given any amount

49:52

of time, I could have never come up with something as massive and compelling as Darwin. And he said

49:57

I don't think any branch of science has ever been created by an individual such as this, such as

50:03

Darwin. So Wallace was in awe of Darwin's synthesis, which was the origin of species

50:12

But they were mutually generous to each other. Darwin, right off on page one, acknowledges Wallace and Wallace's ideas

50:21

And Wallace later, for example, when he writes his first major book, he dedicates it to Darwin

50:27

They are mutual admirers to the point where, for example, Wallace is going to be a pallbearer at Darwin's funeral

50:35

And in their day, this was referred to as the Darwin-Wallace theory

50:39

it's only later that biologists and historians just started kind of forgetting about Wallace

50:47

and crediting Darwin now there might be reasons for that Darwin came from a wealthy family

50:53

the University of Cambridge did a great job at sort of amassing Darwin's collections and

50:58

Darwin's writings and so we just have a better historical record of everything that Darwin did

51:05

But at the time, it was the Darwin-Wallace theory. And I think by today's scientific standards, given the genesis of this theory, the theory

51:14

certainly of natural selection by the two individuals, we would be crediting both of them

51:19

And it's just, you know, it's just the unfortunate sort of, you know, accidents of time that

51:24

people kept talking about Darwin and Wallace sort of faded to the background

51:29

But I really feel in the last 25 years or so that Wallace has seen sort of a renaissance and that people are much more aware of Wallace's huge contributions

51:40

And then Wallace outlived Darwin by 30 years. So he was a really important figure in the discussion of evolution because, you know, this was a brand new science

51:48

It had relatively few advocates at the beginning, certainly people that really understood it well

51:54

And so Wallace played a huge role in getting people to help understand these ideas

51:59

I think if Darwin and Wallace were alive today, they would be so overjoyed

52:05

by the detail with which we understand the process that they first figured out

52:14

They knew variation was important. They knew variation was the fuel of the evolutionary process

52:21

Had no idea how that variation arose. Now, any biologist can point right to the DNA in a newly hatched creature and say

52:30

there's the mutation. That's what's going to make the difference. So our understanding of the material basis of evolution is phenomenally strong

52:38

And I think that would be extremely gratifying to them. But these other manifestations, the role it plays in health and disease

52:48

were nowhere in Darwin and Wallace's minds. So I think that would, again, further astound them that this process they figured out had such widespread ramifications beyond just the natural world

53:04

What we've seen are striking parallels in how life evolves, how our immune system works, and even how cancer arises

53:15

This process of mutation and selection, this staircase. So really, the process that Darwin and Wallace had that first insight into is a universal process

53:29

Wherever there's variation, wherever there's competition, selection will operate. For me personally, as an evolutionary biologist, this just underscores the explanatory power of evolutionary theory

53:42

and the importance of understanding the evolutionary process. You might think, well, the evolutionary process, let's just leave it to the scientists to worry about it

53:51

But I think in our daily lives, you understand that this is why we vaccinate

53:57

This is why we are now developing these strategies against cancer that we, of course, hope everybody will be able to benefit from

54:06

That's a long way from the Beagle voyage of 160 years ago

54:12

But that's fundamentally where Darwin and Wallace have brought us. want to support the channel join the big think members community where you get access to videos

54:30

early ad free

#Biological Sciences

#Ecology & Environment